Ensures the growth of maize; sustains human life.

Origins and Birth

In the cosmic epoch of the Fifth Sun, when the gods had already witnessed four worlds crumble into oblivion and sought to create a humanity worthy of divine sacrifice, there emerged from the sacred council of the Teotl a deity whose very essence would become synonymous with life itself—Centeotl, "Dried Ear of Maize," the Young Lord whose golden kernels would sustain all future generations.

The Nahua creation codices tell us that Centeotl was born from the union of Tlazolteotl, the Great Spinner who weaves the threads of fate and fertility, and Piltzintecuhtli, the Young Lord of healing and calendrical precision. Yet deeper mysteries speak of his true genesis: when the gods threw themselves into the cosmic fire at Teotihuacan to birth the Fifth Sun, their collective essence crystallized into various forms of sustenance. Centeotl emerged as the concentrated divine will to nourish—the living embodiment of the gods' promise that this world, unlike the previous four, would not perish from famine.

In the most sacred account preserved by the priests of Tenochtitlan, Centeotl's birth occurred within the Mountain of Sustenance (Tonacatepetl), where all the world's grains lay hidden since creation. The mountain itself was the body of the earth goddess Tonantzin, and within her sacred womb, Centeotl gestated for four cosmic years—one for each failed world—absorbing the concentrated essence of agricultural potential. When Quetzalcoatl struck the mountain with lightning to release the grains for humanity, Centeotl emerged not as a helpless infant but as a fully formed young lord, his body gleaming with kernels of gold, his hair flowing like corn silk in the wind.

His first divine act was to taste the soil of the new world and declare it suitable for cultivation. His second was to establish the covenant between heaven and earth that would govern all agricultural activity: that humans would offer the first fruits of every harvest to the gods, and in return, the divine forces would ensure the seasonal cycles necessary for continued abundance. His third act was to teach the arts of agriculture to the first humans, showing them how to prepare soil, plant seeds, and perform the rituals that would maintain divine favor.

The priests taught that Centeotl's emergence marked the moment when chaos yielded to cultivation, when the wild forces of nature accepted the discipline of agriculture. His birth established the fundamental principle that would govern Mesoamerican civilization: that human prosperity depends not on conquest or exploitation but on respectful partnership with the sacred forces that govern growth and renewal.

Family

Father: Tlazolteotl (in primary tradition), the earth goddess of fertility, purification, and the spinning of fate; alternatively Piltzintecuhtli, the Young Lord of healing and time

Mother: Tonantzin, the revered earth mother and mountain goddess; some traditions name Xochiquetzal, the flower goddess of love and beauty

Divine Lineage: Descended from the primordial Teotl who sacrificed themselves to create the Fifth Sun

Siblings: Xochitl (goddess of flowers and domestic plants), Mayahuel (goddess of maguey and pulque), Itztlacoliuhqui (god of frost and agricultural dormancy)

Primary Consort: Chicomecoatl, "Seven Serpent," the mature goddess of maize and abundant harvests

Secondary Consorts: Xilonen, goddess of young corn and tender shoots; Ilamatecuhtli, the old woman goddess of death and renewal

Divine Offspring: The Centzonhuitznahua (Four Hundred Stars of the South), minor agricultural deities governing specific crops and farming techniques

Sacred Associates: The Tlaloque (rain spirits who serve Tlaloc), the four directional gods who ensure proper growing conditions, and the calendar gods who govern planting and harvest times

Marriage

Centeotl's sacred marriage to Chicomecoatl represents the eternal mystery of agricultural renewal—the cosmic union between potential and fulfillment that ensures the continuation of all cultivated life. Chicomecoatl, the Seven Serpent, brought to their divine partnership the wisdom of completed cycles and the knowledge of abundance achieved, while Centeotl contributed the vital essence of growth, the irrepressible force that transforms seed into sustenance.

Their relationship transcends mortal understanding of marriage, becoming instead a cosmic principle that governs the entire agricultural calendar. He embodies the hopeful energy of spring planting and the vigorous growth of summer, while she represents the satisfied abundance of autumn harvest and the careful preservation of seeds through winter's dormancy. Together, they form the complete cycle of cultivation—the eternal dance between promise and fulfillment that sustains all civilized life.

The annual reenactment of their sacred marriage during the Ochpaniztli festival involved elaborate ceremonies where young priests and priestesses, temporarily embodying the divine couple, performed ritual unions that ensured the synchronization of human agricultural activity with divine intention. These ceremonies reminded the community that successful farming required not only practical knowledge but also spiritual alignment with the cosmic forces that govern growth and abundance.

Their union also represents the sacred principle that true authority emerges from service—Centeotl's power comes not from domination but from his willingness to transform himself into nourishment for others, while Chicomecoatl's sovereignty derives from her generous distribution of abundance to all who honor the agricultural covenant.

Personality and Contradictions

Authority: Centeotl wielded dominion over the most fundamental aspect of existence—the transformation of seed into sustenance that makes all life possible. His authority was both humble and absolute: humble because he served humanity's most basic need for daily nourishment, absolute because without his blessing, no civilization could survive even a single season. Every kernel of corn acknowledged his sovereignty, every tortilla was an act of communion with his divine essence. His power manifested not through displays of cosmic might but through the quiet indispensability of the agricultural cycle itself.

Wisdom: The Young Lord possessed the practical intelligence of successful cultivation—intimate knowledge of soil conditions, weather patterns, seasonal timing, and the delicate negotiations between human effort and natural forces. Yet his wisdom extended far beyond agricultural technique to encompass the deeper mysteries of transformation: how earth becomes plant, how plant becomes food, how food becomes human flesh and consciousness. He understood the sacred mathematics of growth, the precise calculations of sunlight and rainfall that determine abundance or scarcity. His counsel to mortals always emphasized patience, proper timing, and respect for natural cycles.

Desire: Centeotl's deepest yearning was for abundance shared rather than hoarded—the prosperity that emerges when communities work in harmony with agricultural rhythms and distribute the resulting wealth generously among all members. He delighted in the sight of well-filled granaries, thriving children, and communities that celebrated their harvests with gratitude and joy. His passion was for the multiplication of blessing—each kernel planted becoming hundreds, each act of agricultural devotion returning manifold abundance to the faithful cultivator.

Wrath: When Centeotl's anger was aroused—typically by waste, greed, disrespect toward agricultural processes, or failure to offer proper thanksgiving for harvests—his punishment manifested as crop failure, pest invasions, unseasonable frosts, or droughts that could devastate entire regions. His wrath was never arbitrary but always pedagogical, designed to teach communities the consequences of violating the agricultural covenant. Even his most severe punishments served the ultimate goal of restoring proper relationship between mortals and the forces that sustain life, ensuring that future generations would remember the sacred obligations that accompany agricultural abundance.

Affairs and Offspring

Centeotl's divine relationships extended throughout the agricultural pantheon, each union producing offspring who governed specific aspects of farming knowledge and practice. His liaison with Xilonen, the goddess of tender young corn, resulted in the birth of numerous minor deities who preside over the early stages of agricultural development—the spirits who ensure successful germination, protect young shoots from pests and weather, and guide the crucial transition from seedling to mature plant.

His union with Mayahuel, the maguey goddess, produced the divine principles governing pulque production and the ceremonial intoxication that accompanied agricultural festivals. Their children included the spirits who inhabit fermentation vessels, the entities who determine the quality of ceremonial drinks, and the divine forces that govern the social aspects of harvest celebration.

Through his relationship with various flower goddesses, Centeotl fathered the Centzonhuitznahua—the Four Hundred Stars of the South who serve as agricultural deities governing companion crops essential to Mesoamerican farming: beans, squash, chili peppers, tomatoes, and countless other plants that formed the foundation of indigenous agriculture. Each of these divine offspring inherited specific knowledge about soil preparation, crop rotation, companion planting, and the complex agricultural techniques that supported large populations in challenging environments.

His children also included the spirits that dwell within every cultivated field, ensuring that no agricultural space would lack divine protection and guidance. These offspring manifested as the entities that guide proper harvesting techniques, the forces that govern food storage and preservation, and the divine principles that oversee equitable distribution of agricultural abundance among community members.

The cultural impact of these divine relationships was profound: they established Centeotl as the central figure in a vast network of agricultural deities, creating a comprehensive spiritual framework that governed every aspect of farming life while maintaining the understanding that all agricultural knowledge ultimately derived from the Young Lord's generous sharing of divine wisdom with humanity.

Key Myths

The Discovery of Maize: The most sacred myth preserved in the Popol Vuh and Nahua traditions tells how humanity, newly fashioned from maize dough by the gods, faced immediate starvation because the precious grain remained locked within Tonacatepetl, the Mountain of Sustenance. When human prayers for nourishment reached the heavens, Centeotl heard their pleas and willingly allowed himself to be discovered by Quetzalcoatl, who had transformed into a black ant to infiltrate the mountain's defenses. The Young Lord not only granted Quetzalcoatl a handful of kernels but taught him the secret arts of cultivation, showing how to prepare soil, plant seeds at proper depths, and perform the rituals that would maintain divine favor. This myth establishes Centeotl as humanity's willing partner in survival, the divine being who chose cooperation over hoarding, ensuring that agricultural knowledge would be freely shared rather than jealously guarded.

The Sacrifice of Renewal: During the cosmic crisis when the Fifth Sun showed signs of aging and the agricultural cycle began to falter, Centeotl voluntarily underwent a ritual death and dismemberment to ensure the continuation of cultivation. His body was scattered across the four directions, each piece taking root and producing different varieties of corn adapted to specific climates and soil conditions. His blood became the red corn of the east, his bones the white corn of the north, his skin the yellow corn of the west, and his hair the black corn of the south. From his heart grew the most perfect corn of all—the golden variety that would become the foundation of Aztec agriculture. This myth demonstrates the profound principle that sustained abundance requires willing sacrifice, that the continuation of life depends on the transformation of life itself.

The Journey to Mictlan: When a great drought threatened the Fifth World with destruction, Centeotl descended into the nine levels of Mictlan, the underworld, carrying seeds that glowed like stars in the darkness. His mission was to negotiate with Mictlantecuhtli, the Lord of Death, for the release of trapped rain spirits who had been captured during a cosmic battle. Through nine days and nights of trials—including contests of agricultural knowledge, demonstrations of his power to bring life from apparent death, and offerings of his own divine essence—Centeotl successfully convinced the death lord to release the water spirits. His triumphant return to the surface world, accompanied by the liberated Tlaloque rain spirits, restored the seasonal patterns of precipitation and drought, ensuring that agriculture would never completely fail and that even in the darkest times, the promise of renewal would endure.

Worship and Cults

Centeotl's primary temple complex in Tenochtitlan, known as the Cinteopan (Place of the Corn God), featured elaborate terraced gardens where priests cultivated hundreds of varieties of sacred corn in perfect miniature of the agricultural diversity found throughout the empire. The temple's central pyramid contained chambers lined with gold and precious stones, where the god's most sacred relics were kept: the original kernels given to humanity, soil from the Mountain of Sustenance, and water from the four sacred directions. The complex included vast granaries where the first fruits of every harvest throughout the empire were stored, creating reserves that served both as offerings to the god and as insurance against famine.

His priesthood, known as the Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli (Lords of the Dawn Star), consisted of farmer-priests who divided their time between ritual duties and actual agricultural work, understanding that authentic worship of the corn god required genuine expertise in cultivation. They maintained the tonalpohualli (sacred calendar) that coordinated religious ceremonies with planting and harvesting activities throughout the empire, ensuring that divine and mortal agricultural schedules remained perfectly synchronized. These priest-farmers also served as agricultural advisors to communities, carrying Centeotl's blessing to fields throughout Mesoamerica.

Sacred rituals included the elaborate blessing of seeds before planting, performed at dawn with offerings of copal incense, quetzal feathers, and precious jade. The most important ceremonies involved the creation of tecuitlatl—images of Centeotl molded from amaranth dough and corn meal, decorated with precious ornaments, then ritually consumed by the community in acts of literal communion with their agricultural deity. During the Ochpaniztli festival, communities reenacted Centeotl's mythic marriage through elaborate pageants that could last for days.

His sacred animals included quetzal birds (whose brilliant plumage represented the beauty of mature corn), iguanas (associated with earth's fertility and the patient waiting required for growth), and various butterflies whose life cycles mirrored the transformation from seed to harvest. Sacred plants extended far beyond corn to include all the crops that formed the agricultural foundation of Mesoamerican civilization: beans, squash, chili peppers, tomatoes, and countless other species that thrived under his divine protection.

Local calpulli (neighborhood communities) maintained household shrines to Centeotl where daily offerings of corn meal, flowers, and precious water acknowledged the community's dependence on agricultural abundance. These domestic altars ensured that worship of the corn god remained intimately connected to daily life, making every meal a sacred act and every cooking fire a temple to the divine source of nourishment.

Philosophical Legacy

Centeotl's influence on Mesoamerican philosophical thought was revolutionary and enduring, establishing fundamental principles about the relationship between civilization and nature that guided indigenous societies for millennia. He embodied the concept of teotl—divine force manifesting through transformation—demonstrating that authentic spiritual power expresses itself through service to life rather than domination over it. His example taught that true authority emerges from understanding and cooperating with natural processes rather than attempting to override them through technological force or imperial conquest.

His association with willing sacrifice—both the annual sacrifice of seeds planted in earth and the ceremonial offerings that maintained cosmic balance—profoundly influenced Aztec understanding of reciprocity as the foundation of all sustainable relationships. The corn god's example demonstrated that abundance requires ongoing investment, that prosperity demands continuous engagement with the forces that sustain existence. This principle extended far beyond agriculture to influence political, social, and religious institutions throughout Mesoamerica.

Centeotl's role as the deity who made human civilization possible through agricultural surplus established the crucial indigenous understanding that cultural development and environmental stewardship are inseparable. The great cities, elaborate arts, sophisticated sciences, and complex religious systems of Mesoamerica all ultimately depended on the agricultural abundance that his blessing made possible. This insight led to governance systems that prioritized ecological sustainability and community welfare over individual accumulation of wealth or power.

The philosophical principle that individual and community prosperity depends on maintaining proper relationship with natural cycles influenced the structure of Mesoamerican society at every level. Communities that honored Centeotl's agricultural requirements through appropriate rituals, sustainable farming practices, and equitable distribution of resources consistently prospered, while those that violated the agricultural covenant faced both divine punishment and social collapse.

His example established the understanding that authentic leadership requires deep knowledge of the basic needs of the community and demonstrated commitment to ensuring their fulfillment. Rulers who failed to honor Centeotl—through poor agricultural policy, waste of food resources, or neglect of farming communities—inevitably lost both divine favor and popular support. This principle created a form of ecological accountability that limited the potential for tyranny and environmental destruction.

In contemporary indigenous movements throughout the Americas, Centeotl's legacy continues to inspire resistance to industrial agriculture and advocacy for traditional farming methods that honor the sacred relationship between humans and the earth. His example provides philosophical foundation for arguments that food sovereignty and cultural survival are inseparable, that authentic security comes not from military might or economic domination but from sustainable relationship with the natural world.

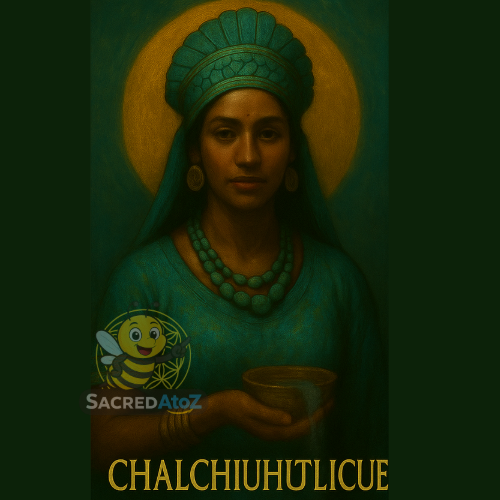

Artistic Depictions

In classical Aztec art, Centeotl appears as a youthful, handsome deity adorned with the golden ornaments and flowing garments befitting his status as divine lord of abundance. His distinctive iconography includes a elaborate headdress constructed from corn ears, marigold flowers, and precious quetzal feathers, often surmounted by a crown of jade representing the eternal nature of agricultural renewal. His clothing typically features intricate geometric patterns woven in gold and green threads, representing both the mathematical precision of successful farming and the vibrant life force that flows through all growing plants.

Codex illustrations depict him in various manifestations corresponding to different stages of the agricultural cycle: as a young man planting seeds in prepared earth, as a mature figure tending growing plants with careful attention, and as a generous lord distributing corn from overflowing baskets to grateful communities. His face paint varies according to seasonal ceremonies, incorporating yellow pigments representing corn kernels, green earth colors symbolizing fertile soil, and red ochre signifying the life force that animates all agricultural activity.

Temple sculptures portrayed Centeotl emerging from corn plants or surrounded by the diverse crops that flourished under his protection. The most magnificent representations showed him as a living corn plant, his body forming the stalk, his arms becoming the leaves, and his head crowned with perfect golden ears. These anthropomorphic depictions taught worshippers to recognize his presence within every cultivated landscape and to understand that successful agriculture required ongoing dialogue with his divine essence.

Mural paintings in agricultural communities frequently depicted elaborate scenes of his mythic adventures: his discovery by Quetzalcoatl within the Mountain of Sustenance, his marriage ceremonies with Chicomecoatl, and his triumphant return from the underworld accompanied by rain spirits. These narrative artworks served both devotional and educational purposes, preserving essential mythic knowledge while inspiring continued reverence for the agricultural covenant.

Contemporary Mexican and indigenous American artists continue to draw inspiration from Centeotl's iconography, often portraying him as a symbol of cultural resistance to industrial agriculture and genetic modification of traditional crops. Modern interpretations frequently emphasize his role as guardian of heirloom corn varieties and traditional farming knowledge, depicting him as a bridge between ancient wisdom and contemporary environmental consciousness. These contemporary artistic works often incorporate traditional techniques and materials—natural pigments, handwoven textiles, and ceramics shaped according to pre-Columbian methods—demonstrating ongoing reverence for the aesthetic traditions associated with his worship.

⚡ Invocation

"Tlazocamati, Centeotl! Ixiptla teotl ic netloc!"

("We give thanks, Centeotl! Divine image dancing in our midst!")

"When golden kernels catch the sacred dawn light, when tender shoots push through blessed earth, when the promise of abundance stirs in every planted field, Young Lord Centeotl rises with the gift of sustenance and the blessing of eternal renewal!"

🙏 Prayer

"Centeotl, Tezcatlipoca nanatli,

Toteouh in nepantla tlalli ihuan ilhuicatl,

Mach timitznotza, tlazohtli teotl!"

("Centeotl, Mirror That Smokes with abundance,

Our god between earth and sky,

Thus we call upon you, precious deity!")

"O Centeotl, Young Lord of the Sacred Corn,

You who transform humble seed into golden abundance,

You who taught humanity the covenant of cultivation,

Bless our plantings with your fertile essence,

Guide our hands in respectful preparation of soil,

Grant us wisdom to plant at proper seasons,

And teach us to share your gifts with generous hearts.

May your corn ears multiply in our fields,

Your golden kernels fill our granaries,

And your spirit of renewal bless our communities

With the prosperity that flows from honoring

The sacred relationship between earth and sky.

Tlazohtli Centeotl, nourish our bodies and illuminate our souls

With the understanding that we are made from your divine substance."