Aztec

The Aztec culture —known to its people as the Mēxica—was one of the most profound civilizations of the Americas, blending art, astronomy, ritual, and divine mythology of the mexican aztec gods into a single vision of cosmic order. The Aztecs believed the universe was a living, breathing cycle of creation and sacrifice, in which gods and humans shared responsibility for maintaining balance between life and death.

Cosmic Vision and the Five SunsAccording to Aztec cosmology, the world has been created and destroyed four times before, each under the reign of a different Sun God. The current era, the Fifth Sun (Tonatiuh), was born through the divine sacrifice of gods at Teotihuacan. Humanity must continually repay that sacrifice through offerings, devotion, and the flow of sacred blood, ensuring the Sun rises each day.

The cosmos was divided into Thirteen Heavens above and Nine Underworlds below, with Earth as the sacred middle plane—Tlālpan—where divine and mortal destinies meet. This layered universe was governed by cycles of duality: life and death, light and darkness, order and chaos.

Major Deities of the Aztec PantheonThe mexican aztec gods was vast and interconnected, filled with gods representing natural forces, human virtues, and cosmic principles.

- Huitzilopochtli: The Sun God and patron of warriors. He represents strength, willpower, and sacrifice. Daily blood offerings were made to empower his battle against darkness.

- Quetzalcóatl: The Feathered Serpent—god of wind, learning, and creation. He embodies wisdom, art, and the renewing breath of life.

- Tezcatlipoca: The Smoking Mirror—god of fate, shadow, and transformation. He tests humanity through trials of desire and illusion.

- Tlaloc: The Rain God—bringer of fertility and storms. Both worshiped and feared, his domain sustains crops and commands the lightning.

- Coatlicue: The Earth Mother—“She of the Serpent Skirt,” giver of life and devourer of the dead. She represents the eternal cycle of creation and destruction.

- Tonantzin: “Our Revered Mother,” a title for the Earth Goddess later syncretized into the Virgin of Guadalupe in post-conquest faith.

- Xipe Tótec: The Flayed Lord—symbol of renewal and agricultural rebirth, wearing the skin of sacrifice to ensure life continues.

For the Aztecs, ritual was not superstition but sacred duty—an act of cosmic maintenance. Through offerings, dances, and ceremonies, they fed the universe itself. Human sacrifice, though misunderstood today, symbolized the ultimate reciprocity between humanity and the gods: the offering of life-force (tona) to sustain the cosmic rhythm.

Daily offerings were made of maize, flowers, copal incense, and blood drawn from priests or nobles. The heart, considered the seat of divine energy, was the purest offering to the Sun.

Festivals and Ceremonial CalendarThe Aztec year, called the Xihpohualli, contained 18 months of 20 days each, followed by five “empty days” of spiritual danger. Each month was dedicated to a specific deity or natural element, celebrated through dance, fasting, and offerings.

- Toxcatl: Festival of Tezcatlipoca, symbolizing renewal and sacrifice.

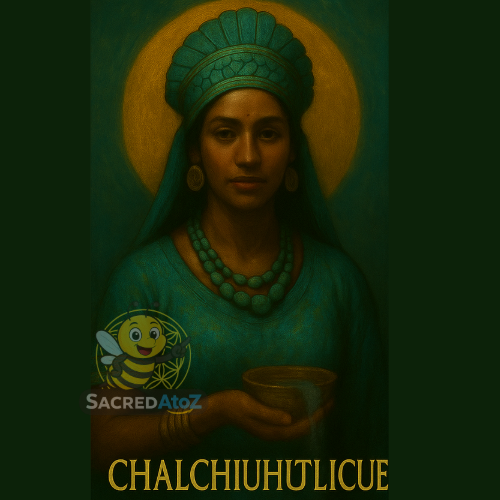

- Tlalocan Ceremonies: Celebrations for rain and fertility, invoking Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue with water rituals.

- Panquetzaliztli: Honoring Huitzilopochtli, the Sun and warrior god—featuring grand processions and sacred hymns.

- Huey Tozoztli: Planting festival, dedicated to the life-giving maize goddess Chicomecóatl.

- Miccailhuitontli & Huey Miccailhuitl: Feasts for the dead, precursors to today’s Día de los Muertos traditions.

Aztec temples, known as Teocalli, stood as earthly reflections of the cosmic mountain. The grand Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán, dedicated to both Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, symbolized the dual balance of fire and water, war and fertility. Atop these pyramids, priests performed rites to keep the sun’s journey secure and the rains abundant.

Philosophy and the Meaning of LifeAztec philosophy—known as Tlamatinime (“wisdom of the knowers”)—saw life as a fragile dream upon the slippery earth. True wisdom was to walk with balance, aware that joy and sorrow are intertwined. To live beautifully (in xochitl in cuicatl—“in flower and song”) was to honor the gods through creativity, art, and courage.

Symbols and Sacred Elements- Eagle: Sun and divine strength, symbol of ascent.

- Serpent: Wisdom and transformation, bridge between earth and sky.

- Obsidian: Mirror of truth and reflection of Tezcatlipoca.

- Maize: Essence of human life—created from corn dough by the gods.

After the Spanish conquest, Aztec beliefs merged with Catholic symbols, preserving ancient cosmology beneath Christian imagery. The Virgin of Guadalupe echoes Tonantzin; crosses mark the four sacred directions once drawn by Quetzalcóatl. Yet the Aztec soul endures—revering the earth, honoring ancestors, and seeing divinity in the rhythm of the sun and moon.

The Aztec worldview teaches that creation is never finished. Each dawn is born from sacrifice, and every act of gratitude keeps the universe alive. In the heart of the Mexica, to live was to serve the cosmic dance of gods and men—forever in balance between life and eternity.