Devas

Hindu

Gods & Deities 19

Amitabha

Buddha of Infinite Light

Avalokiteśvara (Male Form)

Bodhisattva of Compassion

Brahma

Creator God

Dizang

Bodhisattva of the Underworld

Durga

Warrior Goddess

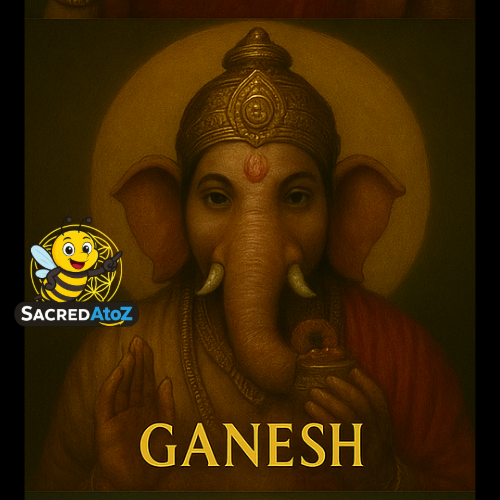

Ganesha

Remover of Obstacles

Guanyin

Bodhisattva of Compassion

Hanuman

Monkey God

Krishna

Avatar of Vishnu

Lakshmi

Goddess of Prosperity

Maitreya

Future Buddha

Mañjuśrī

Bodhisattva of Wisdom

Parvati

Goddess of Love and Power

Samantabhadra

Bodhisattva of Practice

Saraswati

Goddess of Wisdom

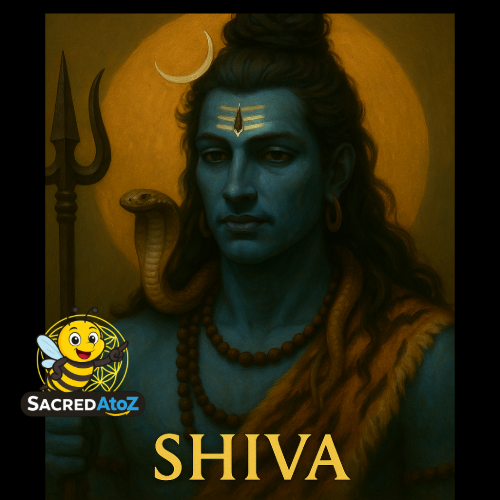

Shiva

Destroyer God

Tara

Goddess of Compassion and Action

Vajrapani

Protector and Lord of Power

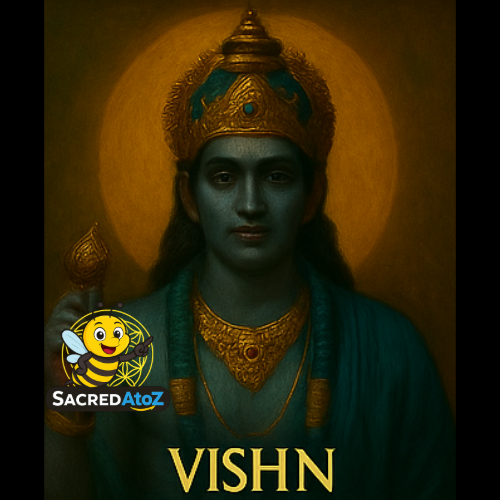

Vishnu

Preserver God

Description

The Devas — A Syncretic Pantheon of Light and Order

The Devas represent the radiant forces of cosmic order and divine intelligence across both Hindu and Chinese traditions. In the Indian Vedic world, the Devas were celestial beings who embodied universal law (Dharma) and natural power. In China, similar luminous spirits evolved under the Taoist and Buddhist systems—immortals, celestial administrators, and protectors of harmony. Over centuries of cultural exchange along the Silk Road, their stories intertwined: Brahmanic cosmology met Chinese Taoist metaphysics, and both envisioned the universe as a hierarchy of divine intelligences maintaining balance between Heaven and Earth.

In Hindu philosophy, the Devas and Devis are aspects of the One—Brahman—manifested through countless forms. The Trimurti—Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer—symbolizes the cycle of existence. Goddesses such as Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Parvati reveal Shakti, divine energy in its creative and transformative modes. The Devas rule the heavens yet remain subject to the law of karma and time; even they reincarnate as the cosmic wheel turns.

In Chinese cosmology, celestial order takes the shape of the Heavenly Bureaucracy. The Jade Emperor governs the celestial court; beneath him serve the Four Heavenly Kings, the Dragon Kings, the Eight Immortals, and innumerable local spirits who regulate rain, rivers, mountains, and stars. Their role is administrative—maintaining Tian (Heavenly order) through ritual propriety and virtue. In Buddhist adaptation, the term Deva was borrowed to denote beings of light—celestial dwellers of higher realms beyond human perception.

Thus, the Devas Pantheon within Godspedia symbolizes a meeting of two great metaphysical traditions. It unites India’s spiritual hierarchy of divine consciousness with China’s ordered harmony of immortal functionaries. Both see divinity as layered and luminous, both revere the laws that govern existence, and both teach that enlightenment is not rebellion against Heaven but cooperation with its sacred rhythm. The Devas, whether as shining Vedic gods or celestial Taoist spirits, personify the moral, natural, and cosmic intelligence that sustains all worlds.

Devas Creation Myth

The Twin Dawn of the Devas — The Convergence of Brahman and the Tao

In the age before ages, when neither stars nor thought existed, the universe was only breath without motion—a silence beyond light, a presence beyond absence. This eternal essence was called Brahman in the sacred tongue of India, and Tao in the ancient wisdom of China. Both were one in truth: the nameless origin from which the Ten Thousand Things would arise. From that infinite stillness came a vibration—soft, resonant, endless. It was the first sound, Om, and it rippled across the void like wind over water, calling the cosmos into being.

In the Indian heavens, the sound became radiance, and from radiance came Narayana (Vishnu), who rested upon the endless cosmic ocean, floating upon the serpent Ananta. In his deep meditation, he dreamed worlds into possibility. From his navel blossomed a golden lotus, and upon that lotus sat Brahma, the creator. As Brahma opened his four faces to the four directions, his breath became the winds, his thoughts the Vedas, his heart the dawn. Thus, the universe began to take shape. From the same act of will arose Shiva, who danced within the fire of time, ensuring that creation, preservation, and dissolution would remain forever in rhythm. And from these cosmic functions emanated the Devas—luminous beings of order, each presiding over an aspect of reality: Agni, Fire; Indra, Storm and Courage; Surya, the Sun; Varuna, the Waters; and Soma, the Moon and Ecstasy. Each was a spark of divine consciousness—radiant, moral, and alive.

Far to the east, in the Chinese dawn of the Tao, the same vibration became Qi, the primal breath. From the void condensed the great cosmic egg, and within it slumbered P’an Ku, the first being. For eighteen thousand years he grew within, pushing Heaven and Earth apart until the vault of the sky stabilized and the land took root. When he perished, his breath became the wind, his eyes the sun and moon, his blood the rivers, and his bones the mountains. From his spirit arose the Jade Emperor, who established the Celestial Bureaucracy, mirroring the order of the Tao itself. Under his reign were appointed the Four Heavenly Kings to guard the directions, the Dragon Kings to command the seas, the Stellar Lords to guide fate, and the Eight Immortals—human beings who transcended mortality through virtue and spiritual refinement.

As centuries passed, the Indian and Chinese currents met along the trade winds and the Silk Road. Monks, mystics, and philosophers exchanged prayers and symbols. The Indian Devas became known in Chinese texts as Tiānshén—Heavenly Spirits; the Buddhist heavens absorbed both worlds, where Indra was called Śakra and ruled the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven beneath the Jade Emperor’s Court. Thus the two cosmologies—one born of sound, one of breath—merged into a vast, radiant vision of divine order.

Creation, in this syncretic pantheon, is not a single event but an eternal unfolding. The Tao moves, and Qi condenses; Brahman dreams, and worlds arise. When the Devas and Celestials sing in harmony, the cosmos thrives—rains fall in their seasons, kings rule with justice, and mortals awaken to compassion. When they fall into discord, chaos spreads as drought, war, and spiritual blindness. Yet always, the cycle renews. The Devas battle the Asuras, light contends with shadow, but the wheel of balance turns ever onward.

From the Lotus of Vishnu to the Mandate of Heaven, the Devas stand as luminous keepers of universal law. They govern not by tyranny but by resonance—each embodying a cosmic principle that also lives within the human soul: fire of intellect, water of compassion, wind of freedom, earth of duty, ether of awareness. Through prayer, virtue, and mindfulness, mortals may align with these forces and ascend toward divinity themselves. To become one with the Devas is not to rule creation, but to remember one’s part in its rhythm.

Thus, the myth of the Devas is both Indian and Chinese—two visions of the same divine current flowing through space and time. It teaches that Heaven is not a place above, but a harmony within: that the breath of the Tao and the sound of Om are one and the same—the eternal pulse of creation, the song by which gods, stars, and souls alike awaken to light.